Automotive disruption – what’s going on in the industry?

“Disruption” in the automotive industry is a topic that now makes it into the daily press on an almost weekly basis. Whether it’s the increasing shift toward e-mobility, the attack of new competitors (e.g. Tesla) on the industry’s top dogs, or even progress on the road to autonomous driving and the mobility of the future. The multitude of sometimes more important and sometimes less important news makes it easy to forget that we in the automotive industry are in the midst of the greatest upheaval of the last 100 years. A loud wake-up call would be much more important for some in the industry than a quiet continuous sound system. At least the bad news – job cuts, plant closures and even plummeting sales figures occasionally highlight how big a shake-up one of Europe’s most important industries is currently undergoing.

The complexity of the change is often not made clear. Even if many have understood that a change will take place, often only individual dimensions are highlighted – for example, the change in drive technology from ecological aspects to e-mobility. It is not just a one-dimensional challenge that everyone in the industry has to face, but many at the same time. And that applies to car manufacturers, suppliers, dealers and workshops just as much as to all other participants in the automotive value chain. In the following, we will take a look at the various disruptions that are simultaneously shaking up all the cornerstones of the business models.

Basically, there are three major changes that are hitting full force at the same time and in interaction with each other: new drive technologies, digitalization and changed mobility.

A. Drive technologies: e-mobility as both a curse and a blessing for the industry

The shift away from the internal combustion engine is the most media-driven change in the industry. It is not just the latest announcements by manufacturers that they will be launching a large number of new electric cars on the market in the next few years with ever better ranges and thus ever better usability. It is also the parallel increase in acceptance on the part of customers. And even if electromobility is still the subject of controversial public debate – one in six new passenger cars registered in Germany was already an electric car or a plug-in hybrid.

But what does this mean for the automotive industry? Taken on its own, it is not yet a major revolution. Tesla has certainly shaken up the industry, but the major OEMs have now all recognized that technological change is coming and are gearing their product portfolios accordingly in the coming years. Volkswagen is already selling more e-cars than Tesla. Legal requirements, such as the EU’s CO2 limits, the internal combustion engine bans on 203x already announced by some countries, and the environmental regulations in China have certainly made a good contribution to setting the change in motion.

But a real revolution? Yes, new know-how is needed. Yes, many employees, especially at suppliers, will lose their jobs. And yes, garages will have to consider what the reduced need for service means for them, and service stations will certainly notice that the stores will be empty if no one comes to fill up anymore. But in principle, everything remains the same: OEMs build cars, suppliers deliver components, dealers sell cars, and there are charging stations where new range can be “refueled” for money.

In contrast to the major disruptions in other industries, the big ones have reacted late here, but have now understood very well that the wheel continues to turn. Many of the previous processes and structures only need to be adapted, they will not become completely obsolete. Even if this still requires huge efforts on the part of everything in the market, it is still feasible for many.

It is also clear to everyone involved that the current state of the art is not yet the end point of electromobility. Whether it’s new battery technologies, the fuel cells or even alternating systems for rapid recharging – the need for research and innovation remains high. Not everyone will be able to afford to play along, and the simplified technology will certainly bring about consolidation in the market.

The fallacy that many people are under in this discussion is that the constant discussion about Tesla’s role in global competition is only about the electric drive. The “problem” of the market competitors with Tesla is rather a completely different one. What does Tesla do differently?

B. Digitization of the car: from the gasoline-powered carriage to the driving smartphone.

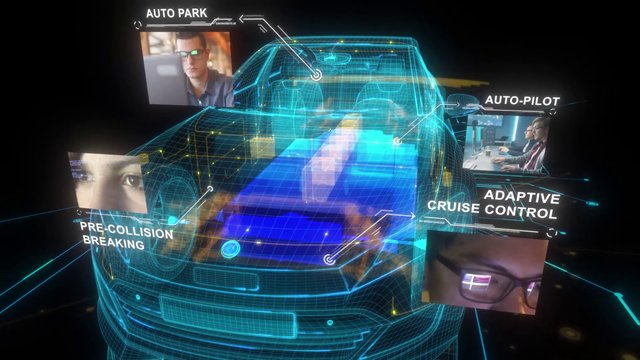

In the 20th century, the automobile was essentially a playground for mechanical engineers. The combustion engine was the core, the bodywork the dress, and even in the chassis, brakes and steering – mechanics everywhere determined the competitive edge. For several decades now, electronics and thus software have become increasingly important. The fact that the German apprenticeship occupation is now no longer called automotive mechanic, but automotive mechatronics engineer, is unmistakable proof of this. This is where the next (the real) disruption of the automotive industry is taking place. With Tesla, software suddenly became the core of the car. The car became an IT product and no longer just a mechanical kit with a few control units.

This is not about new functions, such as navigation, online services, driving assistants or the like. Rather, it is the entire development process and the minimum behind it that is changing and will entail much more far-reaching changes down the line than electric mobility, for example, does per se.

The main difference is the perspective on the “car” product. For the automotive industry, the car has so far been primarily “hardware,” a complex system of mechanical and electrical components that, when arranged to work together, produced a perfectly functioning driving machine that was manufactured in an optimal value creation process based on the division of labor. Alternatively, if you look at the car from a software perspective, it becomes a kind of driving smartphone and the differences quickly become clear. Just as Apple shattered the cell phone market 15 years ago in the meantime, a real revolution may be in the offing here as well in the next few years. With the idea of a software platform of millions of users and countless providers, which allowed a self-contained set of hardware and software to only gradually grow beyond its operating system and basic functions (telephoning, text messaging) to ever new solutions and ever more benefits for customers, the iPhone created the perfect blueprint. What if we imagine something exactly like this for mobility? The car masters its basic function and drives perfectly and safely. Its operating system, however, can be expanded and via a. Huge platforms can be used to create ever new and ever more benefits that did not have to be thought of at the start of the vehicle development project – several years before the start of production. It will be exciting to see which business models and potential benefits will develop as a result.

In any case, the fact is that Tesla’s new way of thinking about how a car is developed and updated is calling the entire previous business model of car manufacturers into question. The way that has worked for decades, selling a car once it has been produced and then already dealing with the development of the next generation, will no longer work in this way. The long-lasting development cycles over several years will become short-term software-driven iterations that accompany a car over its entire lifetime.

The line that manufacturers are treading here remains a fine one. A car cannot simply be brought to market half-finished and then only developed to be fully functional in operation. Tesla is trying to do this in isolated cases – for example, with regard to the so-called “Autopilot”, which promises autonomous driving, but is still prone to errors in its current state – as regular accidents show. Experience has shown that warning drivers that they cannot rely on the system is of little help when the system functions well in the majority of cases. In the end, it will be the mixture between functions that have to work 100% and with a double bottom and many, many additional issues that continuously improve a vehicle further and create consistent added value.

The long-established top dogs still have a long way to go. The classic product development process with a finished product at the end – and only individual minor adjustments during the rest of the product life cycle – is still far too deeply anchored in the DNA of the large OEMs. A change in thinking is only slowly finding its way into the organization, into the processes and oh into the heads. But there is no way around it: in the future, the car will no longer be my product, which once sold will no longer interest the manufacturers. Instead, it will be a matter of regularly offering customers continuous improvement and added value to the product with ever new functions. In terms of that, Tesla is years ahead of the rest of the market in mindset, processes, and software architecture. It doesn’t have to stay that way. The message is getting through and the industry is moving. Processes and organizations will need to become leaner and more agile so that new functionality can actually be delivered to customers every few weeks. Complex

supplier networks and long supply chains will then not always be only advantageous for companies. Instead, the company’s own value creation will once again come more to the fore in many places.

Why do the established manufacturers have such a hard time with the real digitization of their products? Two arguments: on the one hand, the development of a vehicle has always been divided into individual sub-systems that must ultimately function as a complete system. For each subsystem, the geometric and functional interfaces are determined so that everything fits together. From a software perspective, this logic is reversed and the operating system and new software architectures as the heart of a digital car take center stage. So a holistic view is needed – and not just modular individual components such as “infotainment” or superimposed “digital services”. Also, the large variant in the product range and the wide range of options for configuring an individual vehicle by combining individual elements will also be increasingly put to the test in the future.

C. Mobility services and autonomous driving as drivers of change and the third disruption

For OEMs to really be forced into action across the board here, one essential element is missing: the incentive from the customer side to further develop the car not only during product development, but also after the transition to the driver. So far, an OEM has gotten nothing out of this. With each vehicle sold, its work is done. Why bother after that, after all, the customer should prefer to buy the next model in a few years’ time. Only when increasing digitization and new business models succeed in moving the majority away from this, only then will a continuous improvement process for software and functions make economic sense, even after the sale.

At the latest when autonomous driving will be market price for the first time in a few years, this development will be unstoppable. For our mobility, this will be the essential turning point. All experts agree that with autonomous driving vehicles, which no longer require a driver, only “as a service” use will make sense. This means that the utilization of vehicles will increase rapidly. While many cars today are only parked for most of the day, they can then be used more or less permanently without additional cost factors such as a human driver, for passenger transport, courier trips and many other conceivable logistics services. If vehicles are then only used and the revenues only flow back during the life cycle, then the continuous improvement makes even more sense.

The question here is then rather who will determine the autonomous driving market. Today, many OEMs are working on this with a large number of software developers, and the M&A market for specialized providers of sensor solutions and algorithms is booming. Nevertheless, it is the tech companies and special start-ups that currently seem to be technologically further ahead. In particular Waymo as a company of the Alphabet Group (to which Google also belongs) is apparently setting the tone at the moment.

The existing OEMs have to make sure that they don’t lose out and lose their technological sovereignty. If they do, it will be difficult for them to earn money with mobility on the other side. On the contrary, there is a risk that they will degenerate into pure vehicle suppliers to the tech companies. From today’s perspective, this cannot be the long-term business model, especially in view of the consolidation that is likely to occur on the market.

Suppliers must also ask themselves what contribution they can make in view of this change. As a parts supplier, it’s probably not going to get any easier to make viable margins. An investment in the right upcoming technologies and especially in software know-how could pay off. Then there is potential that OEMs may overlook or leave out on their way into the future.

The journey into the (auto)mobile future will be exciting for the entire automotive industry. Whether OEMs, suppliers, retailers or service providers – they all have to earn money at the same time with the existing business, familiar products and the existing organization. At the same time, they will have to actively leave behind many tried-and-tested things and embark on new adventures, new ventures and bets on the future. Not everyone will win – but the industry is far from being written off.