The Chip Shortage in the Automotive Industry Explained

The COVID crisis has shown how thin the ice is for globalized logistics chains. Just-in-time delivery (JIT) became the standard in production companies, especially in the automotive industry, at the latest in the 1990s with the example set by Toyota. Instead of keeping large warehouses where components were stored in stock, tying up expensive capital, they were moved to trucks, rail and ships. With precision down to hours or even minutes, the required components arrive at the factory where they are then immediately incorporated into the final product. In a well-coordinated system of suppliers and manufacturers, capital costs can thus be saved.

However, if there is a delay in delivery, the entire system falters. If the whole thing happens on a global level, where shipments come to a standstill due to border closures or lockdowns, then the factories also come to a standstill. The uncertainty caused by the outbreak of the COVID crisis, and the resulting slump in sales, forced automakers to cancel or drastically reduce their orders. And with it, it forced the supplier industry to take similar steps. Orders were reduced or canceled at all levels.

This led one supplier industry to retool its freed-up capacity for other purposes: the manufacturers of computer chips. Then, a few months after the start of the COVID crisis, when automakers tried to ramp up production again, it was slowed by a chip shortage. It was not a lack of tires or windshield wiper levers that hampered production, but these small electronic components, of which every vehicle today has several dozen to well over a hundred installed.

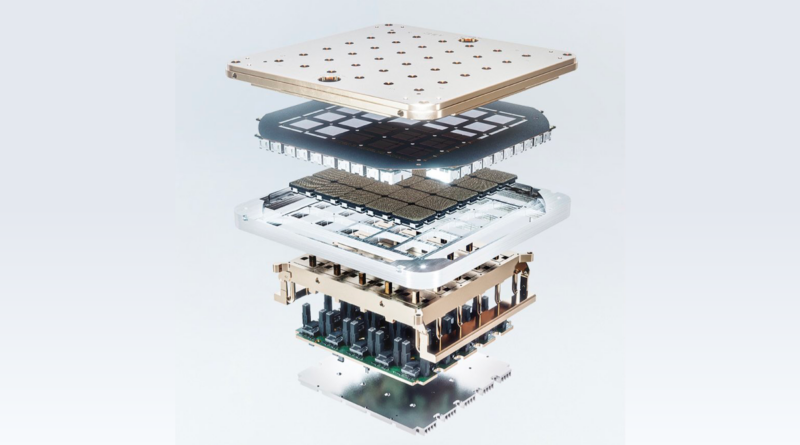

These chips or Electronic Control Units (ECU) are used to control everything in the car, from the window regulator and transmission to the air conditioning system. The ECUs are often built directly into the individual components and installed by suppliers on behalf of the manufacturer. A modern VW Golf alone has about 75 of them.

The Reasons

But why is it that these chips in particular are now in short supply in the automotive industry? This has a number of reasons, ranging from the way the chip industry works to some accidents.

First of all, you have to know that a chip factory and the business behind it work differently than the automotive industry. An automobile factory can be retooled to produce a new model in a matter of months. If the car then “tumbles” to the dealers at the end of the production line, it can take months before the car is sold. In contrast, 18 months must be expected to convert a chip plant. Alignment, calibration, permitting, all the way to clean room requirements all take time. Add to that the special requirements of the automotive industry, which demands a reliability rate of well under 10 in a million chips (for comparison, other applications are one or two orders of magnitude higher), and the chips used there must be able to handle large temperature fluctuations, shocks, acceleration and the like, and things don’t get any easier. But as soon as chip production goes into operation, these chips are immediately used and installed. They have to be, because the chips become obsolete much more quickly and new designs come onto the market.

Thus, the chip and automotive industries are running at two opposite speeds. The chip industry responded to the cancellations by automakers and suppliers by immediately retooling factories to make chips for consumer devices and computers. These had gained demand from the lockdown because now everyone in the home office and home schooling needed a computer, and stay-at-home video game consoles were their pastime. Even more so, both Sony and Microsoft had announced their hotly anticipated new consoles, which had increased demand for chips. All of which explains why even 12 months after car production resumed, manufacturers were unable to ramp up capacity.

To make matters worse, there is a veritable zoo of chips. Not one standard chip is used for the various ECUs, but dozens of different designs. If just one chip is not available, the car cannot be delivered.

Furthermore, fires at a chip supply factory near Tokyo, the icefall in Texas and a drought in Taiwan have brought existing capacities to the brink. And if a container ship – the Evergreen – gets stuck in the Suez Canal in March 2021 and brings shipping from Asia to Europe to a standstill for almost two weeks, there will be even more computer chips missing because they will be floating in containers at sea and cannot be delivered.

Ford, General Motors, Fiat Chrysler (now Stellantis), Volkswagen and Honda appear to be the hardest hit. Others, like Toyota, have not been as dramatically affected. That’s probably because Toyota was better prepared after learning from the massive earthquake and tsunami in Japan in 2011 how sudden, unexpected tremors can disrupt supply chains.

The economic losses from the chip shortage are huge. Ford and GM each expect a $2 billion reduction in profits for 2021.

Possible Solutions

While some manufacturers like Tesla have gone so far as to reprogram firmware and use alternative chips, others have slowed production or are parking finished cars in the stockpile until the missing chip(s) are delivered before the cars can be sold to dealers and customers.

Interestingly, some manufacturers, such as Ford and Porsche, have prioritized their chips for electric cars. The Ford Mach-E and Taycan, for example, received preferential allocation of available chips. The Mach-E’s internal combustion counterpart, the Ford Mustang, even experienced a halt in production.

There are several possible solutions for the automotive industry. One would be similar to what Tesla has demonstrated with its battery factory in Reno, Arizona. Instead of ordering batteries externally, they entered into a cooperation with a battery manufacturer in which they operate a factory jointly and exclusively for their own company. Such mutual long-term cooperation ensures that not only do they research and develop together, but they also maintain capacity in the event of economic fluctuations and they are not retooled by one supplier elsewhere for other customers and industries.

Another approach is to solve the problem on a different level. Instead of using a whole zoo of ECUs and chips in the car for the different components, convergence on one or at most a handful of chip variations would be a good step. This minimizes the risk that the lack of one of the several dozen chip variants will lead to a complete production or sales standstill.

But the chip manufacturers themselves are also tackling the problem, even if the automotive industry, with a 10 percent share of sales, is almost a niche for them. Intel, for example, wants to build two new factories at a cost of $20 billion, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) plans to invest a whopping $100 billion in new chip capacity over the next three years.

Of course, this does not help in the short term, and waiting times and prices for new cars remain high.

This article was also published in German.